I was a man obsessed. I longed to see the sea, to sail quietly across its surface driven only by a puff of wind, to smash through the night in a great tempest. I had become seduced by the books I read describing strange distant lands, postcard-esque shorelines, foreign cultures and a complete absence of bumper-to-bumper rush hour traffic.

William Albert Robinson’s 10,000 Leagues Over the Sea was the first cruising book I read, and it made me want to run away – or rather sail away – from home immediately. Robinson circumnavigated between 1928-1932 on his 32ft ketch Svaap and wrote tales of exploring then-still-exotic Tahiti and spending time with headhunters in Papua New Guinea.

I went on to read Harry Pidgeon’s book Around the World Single Handed. Pidgeon built his modest 34ft yawl Islander in 1917 on the banks of the Los Angeles harbour, not far from where I refit my own boat, Triteia. Pidgeon was the second person to ever sail solo around the world, 23 years after Slocum. Reading Pidgeon’s stories from my own local waters, coupled with the mantra of iconic cruisers Lin and Larry Pardey – ‘Go Small, Go Simple, Go Now’ – was all the inspiration I needed to charge forward with my own dream.

The thought of going with someone else never even crossed my mind in the early days. On my 40th birthday I was recovering from double pneumonia that nearly took my life, and it was on that day I decided I wanted to circumnavigate. Life is simply too short to wait on dreams.

When his rudder failed Frederick improvised and sailed 1,000 miles to Hawaii steering using a towed drogue. Photo: James Frederick

Self reliance

August 20th, 2021

28° 52.019N 131° 20.984W

0200: The winds had vanished, and the boat was being tossed around in a ruckus that made the cabin sound like a box of dishes in the back of a pickup truck. I climbed out on deck and steered us back on course. The wind is so light it seems hopeless because the windvane can’t steer with no wind.

Our course should be 240° on the compass. I steer her to 270° to try and get her moving and suddenly Triteia is screaming through the water like a Nantucket sleigh ride, but when I bring her back to 240°… not a breath of air.

I started to wonder if I actually didn’t know how to sail, before I remembered we were 700 miles offshore so at some point in the last eight days I must’ve known how…

This cycle went on for 30 minutes, with me mostly sitting in my underwear in the cockpit. I would get Triteia moving, climb back into my nest, then she’d wallow again.

Finally I’d had enough, put on my foulies to climb out into the cockpit – only to find that we were sailing perfectly on 240° making fine speed.

The solo sailor, to a certain degree, is always on watch, even when you’re off watch. There are no other hands to quiet the boat, to keep her moving efficiently and on course. The best we can do is be patient, keep the boat balanced and trimmed and hope the squalls are kind to you when they arrive. The trade off is you don’t have anyone else to complain when the wind and seas are not co-operating.

I departed Los Angeles and sailed for the Hawaiian Islands on my 1965 Alberg 30 sloop Triteia in August 2021. The passage ended up taking me 32 days due to total steering loss some 1,000 miles from the Hawaiian Islands. I resorted to steering by drogue for 18 days then proudly dropped the hook off the world-famous Waikiki Beach on O’ahu.

Frederick sailed from Fiji to New Zealand and cruised the Bay of Islands without engine. Photo: James Frederick

Solo ocean sailing means you must face all the challenges alone, but it also means you don’t have to worry about a mate or crew member when all seems lost. I lay adrift for two days during that ordeal, attempting to dive on the rudder to lash a line, to no avail. A task I assumed would be an easy fix proved completely impossible. I was faced with only two options; call for help and scuttle my beloved boat that I had spent the last four years preparing; or find a way to steer her to safety.

I have a chilling memory off imagining her filling with water as I scuttled her and climbed up a rope ladder on the side of a cargo ship. I recall saying “Hell No!” out loud and realised for me, there was only one option; to find a way. And that’s exactly what I did.

If I’d not been alone, I’d have had to consider the well-being of the crew, who would have likely been pushing for rescue when all seemed lost. Being able to see it through alone allowed me the time to figure out a solution.

Was it easy? Absolutely not, all the stresses of that situation laid solely on my shoulders, the weight was heavy and the consequences great. But I prevailed. Hopefully I won’t face future challenges of that magnitude, but if I do I know I’ll find a way. To sail around the world alone, you must be mentally fit and able to control your emotions and anxiety.

Squalls on passage from Los Angeles to Hawaii. Photo: James Frederick

August 30th 2021

24° 56.821N 142° 54.323W

2030: We have already done 23.5miles since noon, that was yesterday’s entire noon to noon run. The sun is golden and threatening to set and I have a 360° view of clouds that look like they were painted as a scenic backdrop for a western set in Monument Valley. But in the place of dusty plains and mountains is the steady rolling sea much further than I can see.

We have had amazing and constant winds all day long and have been charging along or surfing down waves since sunrise. I had a wonderful visitor today – a White-tailed Tropicbird! He was majestic and beautiful and attempted to land atop my mast, but its motion was too unruly.

Article continues below…

One of the biggest gifts you can give yourself is time. Time to do the things you love, time to…

Personal preparations and sailing skills are still the biggest part of planning to sail around the world. Knowledge and competence…

Anxious passage

After eight months cruising the Hawaiian Islands and making repairs to my rudder, I pointed my bow towards the Southern Cross and beat into the tradewinds to make enough easting to visit the ‘Dangerous Isles’, the legendary Tuamotu archipelago in French Polynesia.

The distance between Kona on the Big Island of Hawaii and Rangiroa in the Tuamotus was almost the exact same distance I’d sailed between Los Angeles and the Hawaiian Islands; 2,300 miles.

I was fairly anxious leading up to this passage, after what I’d experienced sailing to Hawaii. I carried enough water and provisions for more than 40 days at sea, had equipped the boat with new sails, larger solar panels, lithium batteries and an all-electric galley while in Honolulu. I loaded up every spare I could manage, stowage on a 30ft boat being minimal at best. I made one last trip to the grocery store the night before departure and hoped that I’d remembered everything.

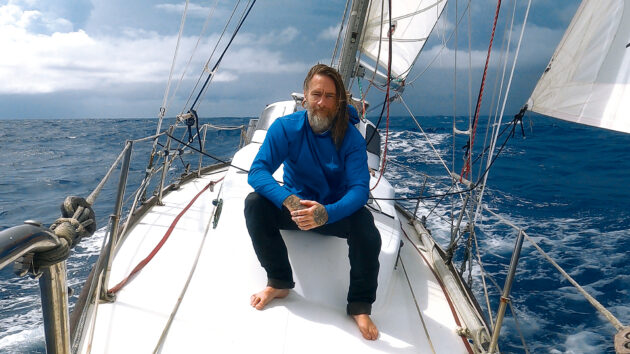

‘To sail around the world alone you must be mentally fit’. Photo: James Frederick

June 30th, 2022

14° 51.373N 152° 14.201W

1800: A sailor who chooses to wander the world’s watery surfaces in a small boat must have two characteristics; 1. The inability to distinguish between feelings of misery and comfort and 2. A very poor memory, for if they could accurately recall the misery of their past voyages they should never set to sea again.

The first eight days of the passage were the worst I have experienced before or since. To visit the Tuamotus, I had to beat my way east into the tradewinds before reaching the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) to make my easting. It was abusive and exhausting, even in my full-keel boat which takes the seas well.

Once I reached the ITCZ and crossed the equator I was able to ease the sheets and had glorious sailing all the way down to French Polynesia.

The Tuamotus ended up being worth the beat. From exploring uncharted motus in the Lagoon of Rangiroa to swimming alone with manta rays at an abandoned pearl farm on Tikehau, these sparsely populated atolls were the highlight of my time in French Polynesia.

I went on to visit the legendary island of Tahiti, dropped my hook at Mo’orea, surrounded by its otherworldly landscapes. I sailed on to Hauhine and visited its sacred blue-eyed eels and visited Polynesia’s most significant religious site, Taputapuatea on Raiatea.

I ended my time in French Polynesia with two weeks at Bora Bora where my 30ft yacht was exempt from the anchoring restrictions (any boat under 10m is allowed to anchor and is not restricted to moorings) – a wonderful surprise benefit to seeing the world on a small boat.

Triteia anchored off the uninhabited islet of Motu Faama in the Rangiroa atoll, French Polynesia. Photo: James Frederick

As I prepared to sail for American Samoa I found I was really looking forward to the ‘short’ 1,100-mile distance. I realised I had none of the anxiety that had weighed on me on the previous big ocean passages. I was far more comfortable now with so many miles in my wake. I knew the boat and what she was capable of, and the moment I cleared the pass at Bora Bora I set the sails wing-and-wing and enjoyed a lively but fast 10 day passage.

I wasn’t free of problems, but I found myself being far more confident and relaxed, even when things broke or got crazy.

July 25th, 2022

14° 58.156S 147° 38.293W

0700: I awoke as the sun was making his entrance. I popped my head out of the hatch and was greeted by a gorgeous sunrise in the making.

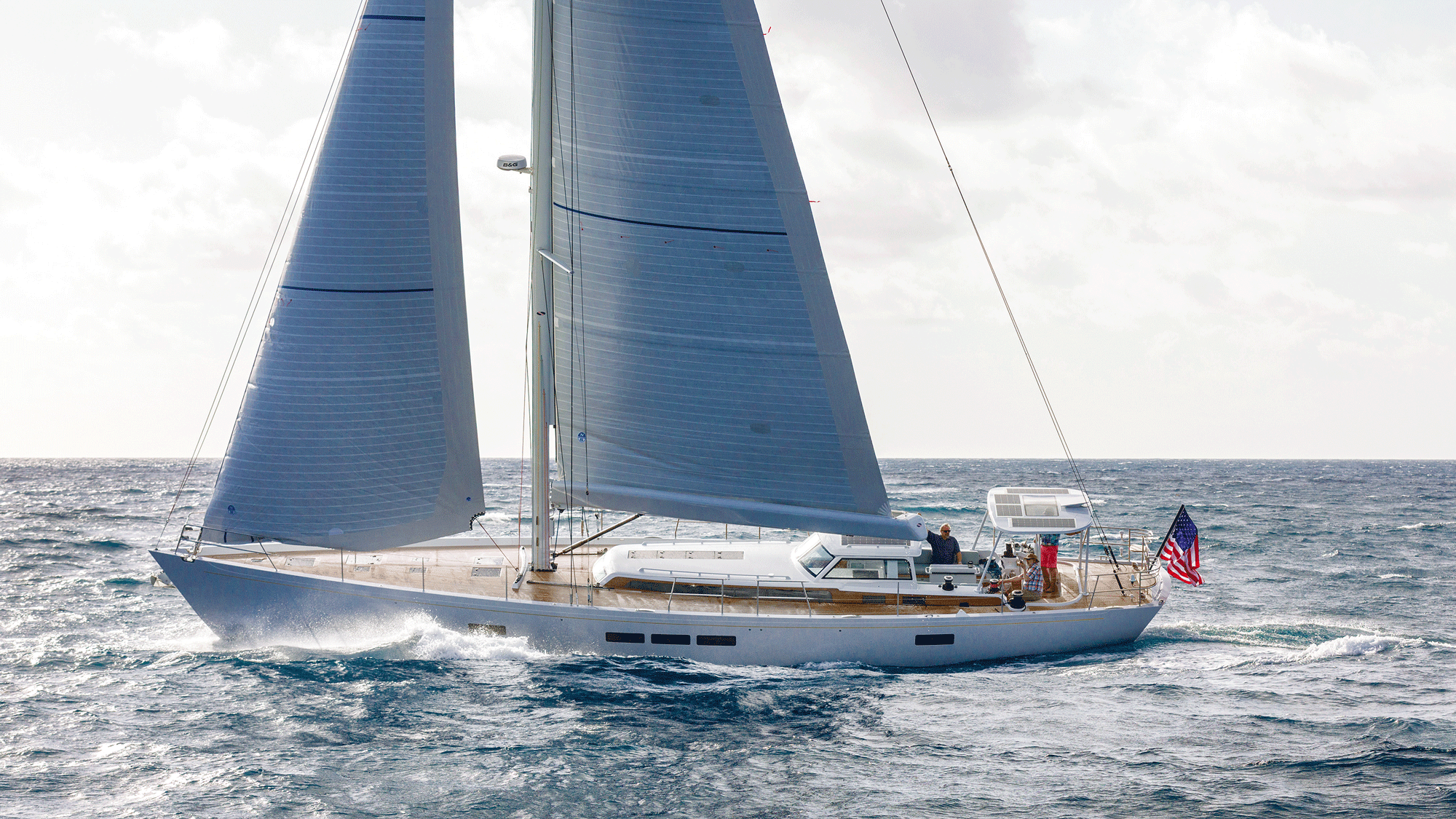

Climbing out of my berth into the cabin, the story book clouds over the lagoon slowly began to glow pink and then orange. A $75million superyacht sat anchored astern of Triteia in deeper water. I realized we both had the same view. I also realised no one was on the deck of the superyacht watching the sunrise.

Life on an angle – meal prep in Triteia’s compact galley. Photo: James Frederick

Heading east

Departing French Polynesia I ran before the strong tradewinds to Pago Pago on American Samoa and on to Fiji. When I departed Los Angeles for this circumnavigation I made myself a promise to say ‘Yes’ to any experience that wouldn’t land me in a foreign prison.

For most of my life I have carefully chosen what I would and wouldn’t do, to avoid being in a situation I didn’t want to be in. Now I find myself in places I would have never agreed to visit with my old mindset. Sometimes they lead to me being uncomfortable or are simply not fun, but more times than not I find myself having amazing experiences that I will cherish the rest of my life, all because I opened myself up to saying ‘Yes’ and just going with the flow.

When you’re solo this is easier to manage and, if you find yourself stranded in the middle of nowhere in the pouring rain, there is no one else there to be mad at you. It’s known as ‘Type 2 Fun’.

While in Fiji my engine began to fail, and though I got it running long enough to get Triteia outside the barrier reefs of Fiji, it never started again. Sailing south to New Zealand, out of the reliable tradewinds and into the variables I found myself battling low pressure systems with sustained winds of 40-plus knots regularly followed by days of light winds.

I sailed into the Bay of Islands of Aotearoa in a building gale and accepted a good samaritan’s offer for a tow the last mile to the quarantine dock. I spent the next three months cruising the Bay of Islands engineless, riding out four tropical storms and one cyclone under anchor.

Reefing down ready for stronger conditions in the Tasman Sea. Photo: James Frederick

Circumnavigating on a small boat forces us to keep up a quicker pace, due to our slower speeds. Larger yachts with big sails and bigger motors can linger in places longer and make quicker work of the ocean passages. While in the tradewinds, Triteia averages about 110 miles a day on ocean passages with 138 miles being her record best.

This means I need to set realistic goals when it comes to passage planning for the year. In the South Pacific, all sailing yachts need to be out of the cyclone danger zone by the first of December. The distance between Tahiti and the next cyclone-free safe harbour is 3,000 miles on the shortest line. I chose to sail south to New Zealand, while some boats continued west through the Torres Straits for Indonesia or the Indian Ocean.

A year in Aotearoa

I had originally thought I would only be in New Zealand for four months but was amazed at what a vast cruising ground it was, so decided to spend more than a year exploring both the North and South Islands. I visited 77 different anchorages in that time, the highlight being Marlborough Sounds, an elaborate network of coves and inlets whose deep waters are populated with well-maintained mooring balls. (I joined Pelorus Boating Club and received a printed guide showing the locations of more than 100 balls to choose from).

Most of the anchorages provide 360° protection and, even with the intense williwaws that blow down from the surrounding mountains, the sea state never packs much of a punch. But to get here you must cross the infamous Cook Strait.

Triteia anchored in Kāne’ohe Bay, O’hau in the Hawaiian islands. Photo: James Frederick

December 7th 2023,

40° 47.810S 173° 52.086E

0300: I am resting and licking my wounds. Yesterday’s crossing across the notorious Cook Strait was spicy to say the least. Neptune gave me a wink and a nod as I crossed into the Roaring Forties just to remind me what he can serve up.

Yesterday’s forecast called for 17-knot winds sustained.

What I saw was closer to 25 sustained with gusts of 35 and some longer sustained gusts of 40-plus around midnight. Seas were in proportion to the wind, so I am guessing 2m most of the time with some 3m-plus thrown in from time to time, and all very short period, which is what makes them mean.

Cook Strait is a supersonic acceleration zone. The Strait goes from being 60-miles wide to just 11-miles wide at its most narrow point. Combine that with the mountains, and hills on either side and the wind and seas are squeezed into a narrow slot. The depths also go from 3,000ft to 300ft in less than 100 miles. This is like putting your thumb over the end of a garden hose; the wind accelerates in speed, as do the currents, and the waves stand up as the seas drive into the shallows.

We had two low level knockdowns yesterday. The first one was a very large wave that hit with great force and threw Triteia on her side. Everything from the port side flew at high speeds to the starboard side. I was sitting up in the normal spot when the hit happened.

Every piece – and I mean EVERY piece of silverware – flew across the cabin, somehow didn’t hit me. I looked down and saw all five of my large filleting knives, in sheaths thankfully, laying in my lap.

The second knockdown was slow and quiet, basically just a giant swell that rolled Triteia completely on her side. At that point there was nothing left on the port side to fall so nothing went flying. I know Triteia’s entire bottom was out of the water because I heard it make a great splash when the boat righted itself. I laughed at how absurd it was.

James Frederick is a solo sailor circumnavigating in his 1965 Alberg 30 sloop Triteia. Photo: James Frederick

I departed New Zealand from Nelson and made my way out into the Tasman Sea. I’d been nervous about this particular passage for more than six months as the Tasman has a reputation for being a deadly serious stretch of water. I’d spoken to half a dozen Kiwi sailors who had ‘crossed the ditch’ numerous times and all suggested I try and ride the top of high pressure systems all the way across to Sydney.

Following this advice, I ended up having the most pleasant ocean passage I have ever had, making my way north out of the Roaring Forties to complete the 1,200-mile passage in 13 days. I sailed through the Heads into the protection of Sydney Harbour at 2am smiling ear to ear knowing I had successfully crossed the entire Pacific Ocean solo on a 30ft boat.

“Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage,” wrote author Anais Nin. I find this sentiment to be very true when it comes to seeing the world by sail. We must live our lives to the fullest, and for me this means seeing as much of the world as I can from my modest 30ft sloop.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.

Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·