PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by Adpathway Denis Poroy-Imagn Images

Denis Poroy-Imagn ImagesHere’s Nick Pivetta’s signature pitch:

Or maybe it’s this one, complete with a skip-off:

OK, the man just likes skipping:

You might wonder why all of his signature pitches are tossed down the middle for called strikeouts. That’s because Pivetta is the league leader in a statistic I didn’t know I loved until I looked it up: called strikeouts on pitches right down the pipe. He’s the 2025 leader. He’s the leader over the past five years, in fact. Keep your reality-distorting sweepers and letter-high four-seamers; Pivetta gets the job done more simply.

This feels like an impossible skill to cultivate. You hear all the time about pitchers going into a lab somewhere and adding velocity or spin. New pitches? They’re a dime a dozen these days. A starter who hasn’t added a sweeper and cutter sticks out like a sore thumb now that technology and training make it easier than ever to branch out. Every year, the sliders get slidier, the curveballs get curvier, and the fastballs get faster. Meanwhile, Pivetta throws 94-mph “heaters” down the middle for strike three. How??

Some of it is just audacity. Take that first strikeout, a grooved cutter to a guy with 99th-percentile bat speed. Jordan Walker chases too much and doesn’t make enough contact when he swings. No one in their right mind would throw him a fastball down the middle in an 0-2 count. He’s seen 89 0-2 pitches this year; five of them have been fastballs over the heart of the plate. You can forgive him for not expecting the challenge.

Some of it is sequencing. Let’s stick with that Walker strikeout. In their first meeting of the game, Pivetta pounded Walker with breaking balls away, four out of the six pitches in the at-bat. In their second meeting, Pivetta hung a sweeper up and away, but Walker hit it into the ground for an out. The matchup seemed to mostly be about Pivetta’s spin against Walker’s ability to lay off it.

To start our fateful at-bat, Pivetta threw Walker two four-seam fastballs, both high and on the inner half. Walker’s a big league hitter; he can put two and two together and expect a diving sweeper. And then Pivetta broke out the spin! But it was a cutter, which mimics slider spin but stays true in its flight path instead of breaking and diving. Walker held himself back like he was trying his hardest not to swing over a pitch in the dirt – but the pitch was down the pipe. Checkmate.

All of Pivetta’s called strikeouts have similarly plausible explanations. Jose Herrera got a steady dose of low curveballs early, so he didn’t expect a high curveball late. Jon Berti was thinking about the outside corner because Pivetta had been attacking him there, so he too laid off expecting something bendy. You could go through all of Pivetta’s 22 (twenty two!) called strikeouts on middle-middle pitches this season and find some kind of narrative.

Of course, I could make these narratives up about almost any sequence. There are so many counterfactuals and Princess Bride-style levels of thinking that almost any order of pitches could theoretically lead to a batter getting locked up in a two-strike count. Three straight fastballs? Surely, he’d never throw a fourth. Three straight fastballs? Obviously, the trend is your friend, and another one is coming. I’m not even sure which of those is more compelling, which speaks to the difficulty of explaining via storytelling.

More relevant, then, is what broad skills help Pivetta accomplish this sleight of hand. Lots of pitchers mix up their offerings and play one off of the others. Lots of pitchers have the same fastball/slider/curveball/cutter mix. He doesn’t throw in the zone particularly often or particularly rarely. His pitches aren’t noteworthy when it comes to keeping opposing bats on shoulders; his chase and in-zone swing rates are close to league average. Opponents make contact at an average rate when they swing. The broad aggregates make Pivetta seem unremarkable, but he’s clearly doing something to bewilder opposing batters.

One Pivetta advantage: He’s more daring than opposing hitters can possibly imagine. Out of 126 pitchers with sizable starting workloads, Pivetta is eighth in heart-of-the-plate rate in two-strike counts, in the 94th percentile. In other words, he’s throwing it down the middle in unlikely situations more than almost anyone else. In every count that doesn’t feature two strikes, Pivetta is a lot closer to average, with a 67th-percentile heart-zone rate.

That backwards approach is definitely making Pivetta’s stuff play up. You can advance scout all you want, produce packet after packet that says “watch out for this guy sneaking you a fastball when you least expect it.” That’s all well and good, but hitters have spent thousands of hours telling themselves not to fall for breaking balls in two-strike counts. They’ve spent thousands of hours swinging over those stupid breaking balls in those stupid two-strike counts and ending up with strikeouts for their troubles. They’ve told themselves “don’t chase, don’t chase, please please don’t chase” under their breath. And then you meet a guy lobbing them down the middle and your mind scrambles.

To be fair, it’s not like half of Pivetta’s two-strike counts end with him meatballing his way to a strikeout. He’s thrown 683 pitches in two-strike counts to rack up those 22 meatball called strikeouts. When he ventures over the heart of the plate with two strikes, batters usually swing; 87.4% of the time, to be precise. But that’s lower than the league average swing rate in that situation (93%). In fact, Pivetta’s mark is nearly the lowest in baseball. Only two out of the 114 pitchers who have tossed at least 100 middle-middle pitches in two-strike counts are drawing swings less frequently.

That sounds counterintuitive. Even weirder, the guys who draw swings less often than he does also like to flood the zone when they reach two-strike counts. My guess? It’s a selection effect. Pitchers with the requisite sequencing, approach, stuff, and deception to make batters short-circuit and watch strikes fly by naturally throw more of these pitches. Why would they do anything else? It works!

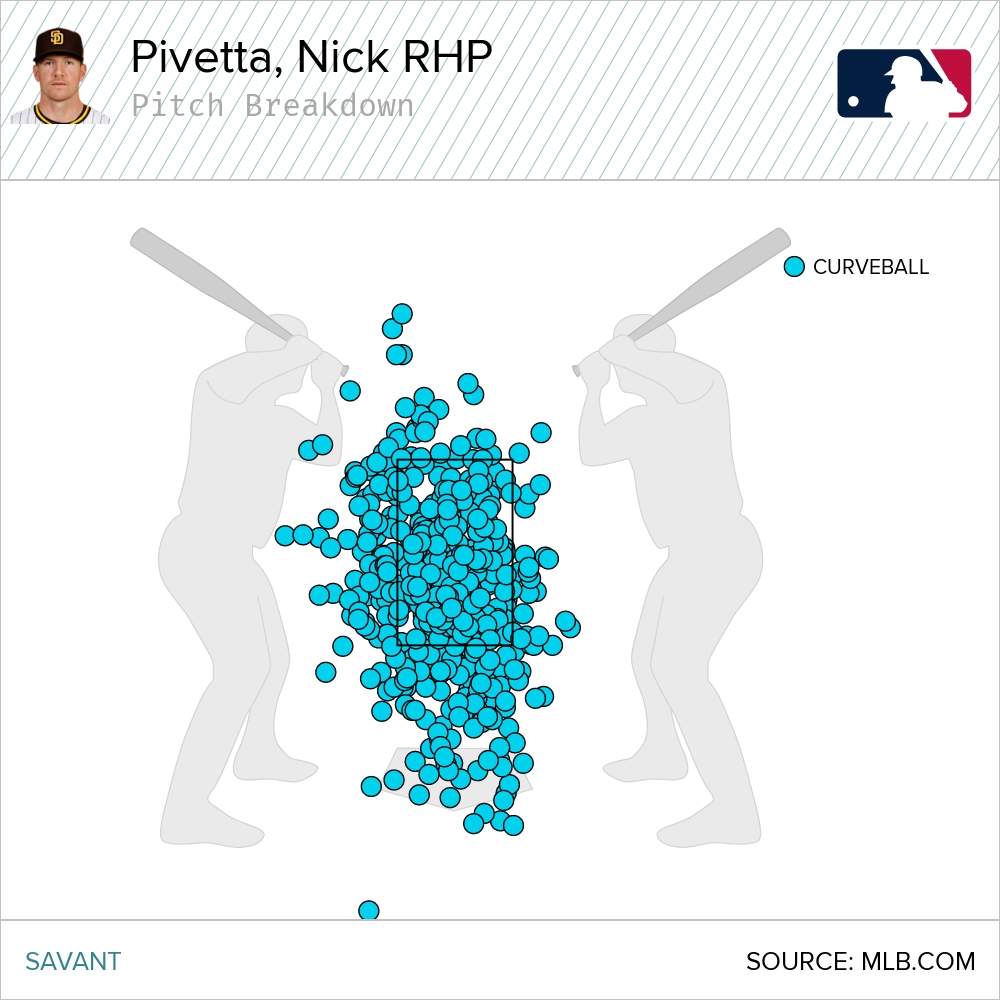

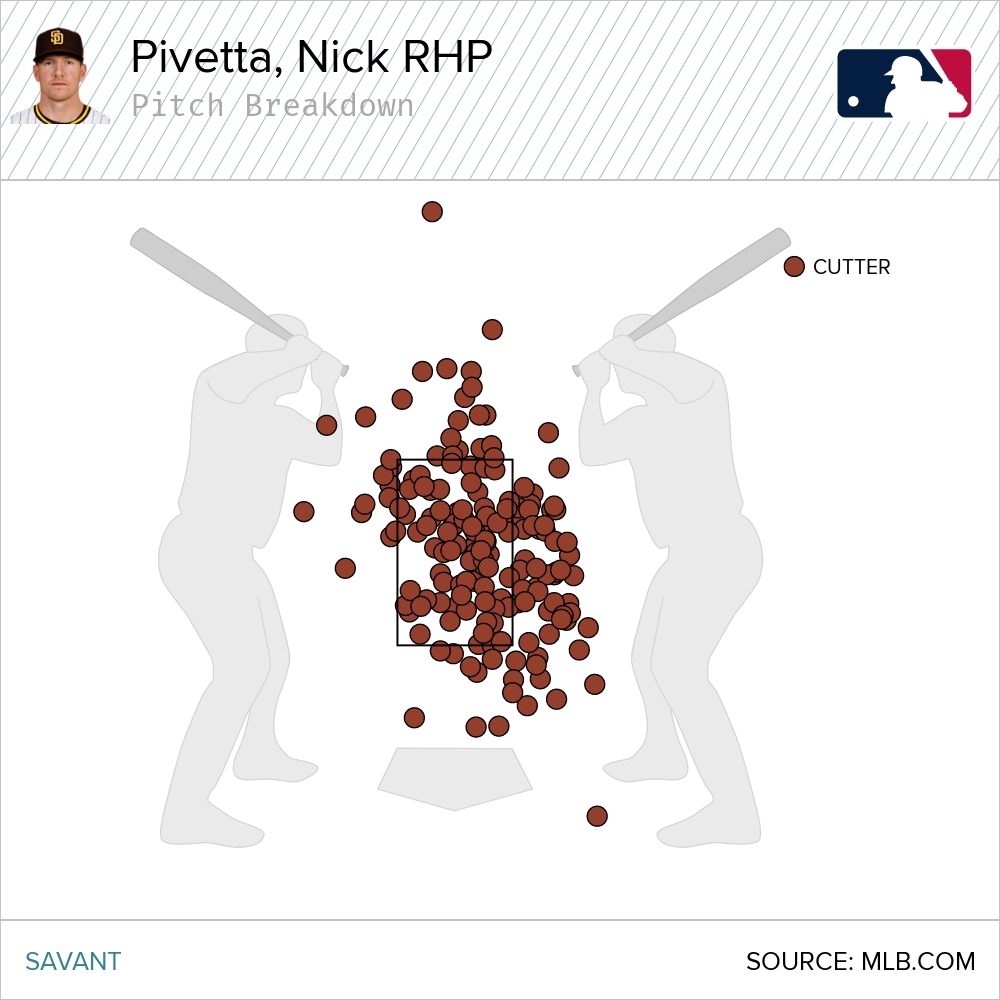

One prerequisite for making this work: the ability to move all of your pitches around the plate. If you’re bouncing your curveball every single time, that makes the opposing hitter’s job a lot easier. Likewise, if you only work low in the zone with your fastball, the batter will be able to eliminate potential offerings and react to your low heater more quickly. Pivetta throws whatever he wants, wherever he wants. Take a look at the location of the 500ish curveballs he’s thrown this year:

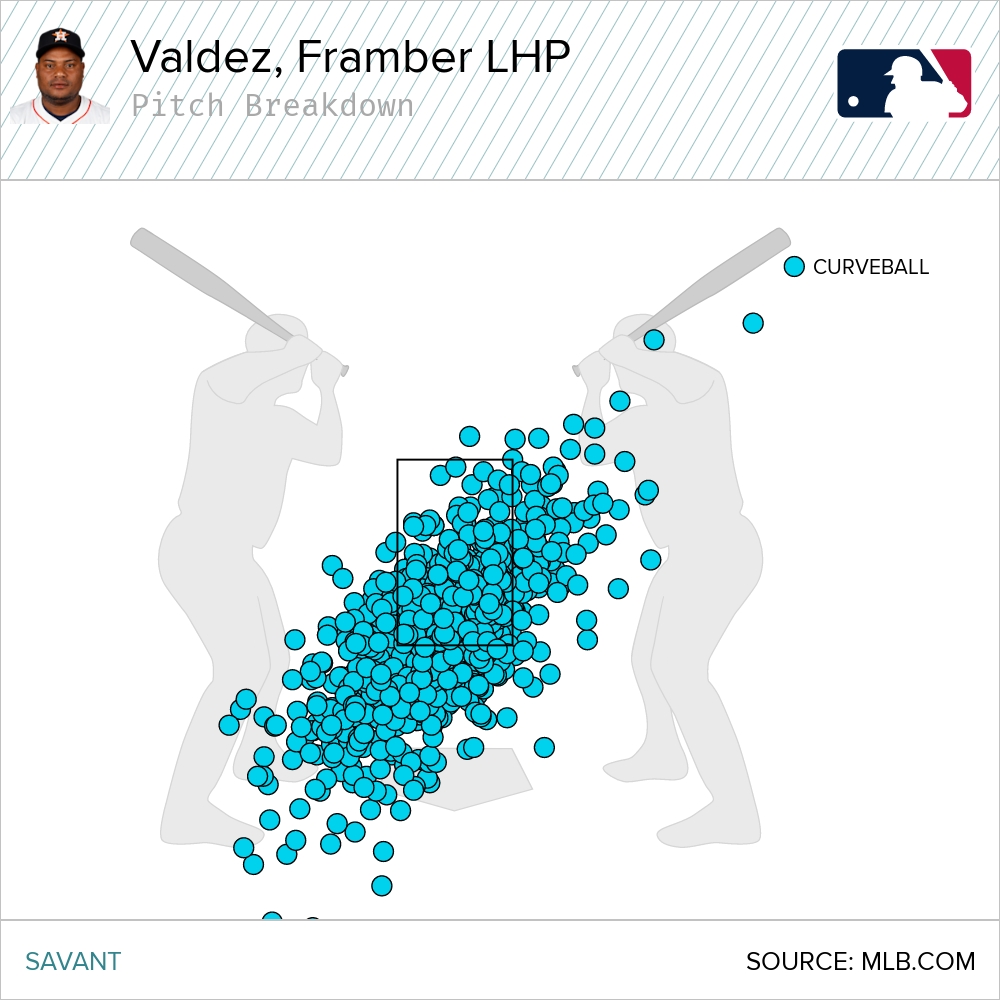

The best way to describe that shape is “blob-like.” There’s no clear center of mass, no clear path he’s spinning the curveballs along. There’s a big cluster up at the top of the zone, another in the middle, and plenty of pitches bounced. He hits every area of the zone, and misses off each of the edges somewhat symmetrically. The ball could end up anywhere, in other words. Compare that to Framber Valdez, owner of one of the best curveballs there is:

Valdez’s curve follows a pattern. He has it on a string, dotting the low corner with frequency, and when he misses with it, he generally does so along that same axis. From his lefty arm slot, you can think of his curveball as following a consistent path homeward with occasional alterations. Valdez’s curveball is better than Pivetta’s, whether you’re looking at a pitch model, actual results, or even the eye test. But Pivetta’s is more unpredictable, and yes, he draws bad takes with it more often than Valdez draws bad takes with his.

All of Pivetta’s pitches are like that. Few pitchers throw more high sweepers than he does, because he moves his target around instead of aiming low and glove side. He uses his four-seamer all over the zone. Not that he throws a ton of cutters, but when he does, you guessed it, it looks like a Rorschach test:

I’ve shied away from telling you how well Pivetta does overall on these grooved pitches with two strikes. Yes, he throws them a lot. Yes, he racks up a ton of called strikeouts as a result. But is the trade-off good? Batters only swing at 87% of these pitches, but 87% is a lot! On the other hand, 22 called strikeouts is a lot, too. It’s a tough question. Think it over. While you do, here’s Dominic Smith taking two pipe-shot fastballs:

The answer: It’s incredibly effective! All of his heart-zone pitches in two-strike counts, the ones that draw takes and the ones that draw swings, have added up to 11 runs of value this season. In other words, the results he’s gotten from them have prevented 11 runs relative to what an average pitcher would have given up in those situations. That’s tied for the best mark in the majors with Max Fried, himself a connoisseur of unexpected strike zone attacks. He’s been six runs above average per 100 such offerings, a completely unsustainable rate. No one’s six runs above average per 100 pitches in the long run – think about how many runs the average pitcher allows per 100 pitches and you’ll understand why very quickly.

In fact, Pivetta is one of the most effective two-strike pitchers, period. Here are the 10 most effective pitchers when it comes to limiting offense in two-strike counts:

Best Pitchers in Two-Strike Counts, 2025

This season, 329 different pitchers have thrown 200 or more pitches in two-strike counts. Nick Pivetta is the eighth most effective, and most of the guys ahead of him are relievers pumping 100-mph fastballs for an inning at a time. (Trevor Rogers is great: Noted.). Pivetta’s strategy isn’t some novelty. It’s one of the most effective in the major leagues. And it’s “throw pitches in the easiest place to hit them in the counts where there’s the least reason to throw them there.” Pretty delightful.

3 hours ago

1

3 hours ago

1

![[MLBTR] Félix Bautista Undergoes Shoulder Surgery, Expected To Miss 12 Months](https://external-preview.redd.it/XgZuFls_SLyVAifW5OnzXGPYo7Nn_Xp1P-VMC-wa-DM.jpeg?width=640&crop=smart&auto=webp&s=b6473a34da7981ba3de80cd0f9f21118b9c5522c)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·