It’s 21 years since my old friend Andrew Bray, then editor of Yachting World, asked me to produce a six-part series taken from nautical literature entitled Great Seamanship. We started with Bernard Moitessier’s description of a Southern Ocean survival storm, then contrasted this with a whimsical tale of high latitude adventure from Rockwell Kent.

From there, my wife and I continued to plunder the shelves of our own extensive library. As the column evolved, it became clear that readers were enjoying it and the supply of material showed no signs of drying up, so we carried on past the original shut-off date.

Year followed year, the content moved from historical accounts to more up-to-date stories, and we branched out so that from time to time we could feature a delightful piece of writing with little to do with gigantic seas or unimaginable winds. We featured sea scouts, clipper ship captains, titled ladies and ‘duffers on the deep’. Each served us with rich entertainment while expanding our knowledge, but all good things must come to an end.

And so it is with Great Seamanship. This is to be my last column under this heading.

From the beginning, I have avoided any temptation to feature my own work in these pages, but for this final submission, I am breaking the mould. In 1988, my book Topsail & Battleaxe won the Best Book of the Sea award.

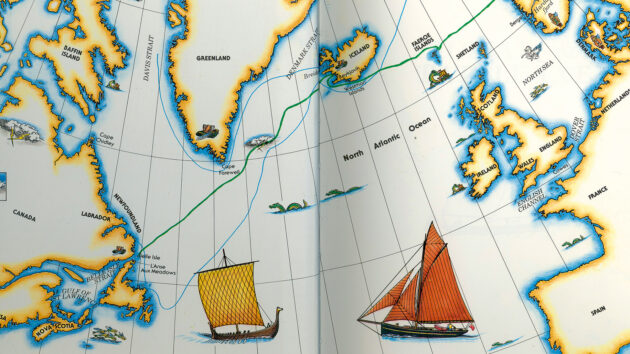

It described two voyages. The first, encompassing three generations, covered the Viking discovery and attempted colonisation of North America in the 10th and early 11th centuries.

The second, a mere summer long, was the trip I made with my wife, my then-four-year-old daughter, and a crew of considerable character in their wake. This took place in 1983 with the boat I owned at the time – an unrestored 1911 pilot cutter, of 35 tons displacement, gaff rigged with canvas sails.

Topsail & Battleaxe, by Tom Cunliffe,

audiobook available from tomcunliffe.com

Rather than selecting an extract from the part of the book describing storms and ice off Greenland with my highly colourful crew, I have instead opted for one of the greatest feats of seamanship of all time which is analysed in the book, the voyage of Bjarni Herjolfson.

His vessel was a 55ft knarr, typical of the redoubtable Norse merchant ships of his day; commodious, seaworthy and surprisingly close-winded, she became the first vessel from Europe to sight America.

Bjarni and his father Herjolf ran a trading business between Norway and the relatively new colony of Iceland. Bjarni took care of the seafaring, his father operated the onshore side of the show at home in Iceland.

Meanwhile, Eirik the Red, a first-generation Icelander was following his father’s footsteps by indulging in a little murder and mayhem. To avoid the inevitably unpleasant consequences, Eirik opted to leave and set up a new community in south-west Greenland. For reasons obscure, Herjolf went with him, leaving a vacuum in the business when Bjarni arrived in Iceland loaded with trade goods.

The evidence for my reconstruction of Bjarni’s subsequent voyage comes from the Icelandic sagas. These have been picked over by many authorities who have drawn various conclusions. I have approached the matter from the point of view of a seaman who has been there in a sailing vessel of modest performance and, as folks say, ‘done it’.

Bjarni’s knarr, of course, had neither log nor compass. Although he had no longitude, he was able to determine a rough comparative latitude – no numbers you’ll note – by using a stick held at arm’s length in Bergen and making a mark at the height of the pole star.

Since both that port and Cape Farewell in Greenland stand at the same latitude (around 60°N), and Polaris does not move significantly, it follows that a heading of east or west from one will find the other. In the absence of measured miles, the Norse at this time reckoned their distance run on the basis of a day’s sailing. This was known as a doegr, which I take to be 24 hours sailing for an average vessel.

In the real world of sail and oar, this would be around 100 miles. A knarr driven hard with a fair wind can manage far more, but one must look to the average with no auxiliary engine. In any case, it is a flexible measurement.

Illustrations of Bjarni and his voyage are inevitably in short supply, so we have used archive photographs from my own trip to brighten our darkness here. We join Bjarni and his crew arriving in Iceland to discover that the expected backup and sales team have flown the nest.

When Bjarni Herjolfson’s deep-loaded knarr fetched up in Iceland in the summer of 985 her arrival was the culmination of a two-year voyage. In addition to anticipating payday, his men were looking forward to being reunited with their loved ones and seeing how affairs had proceeded in their absence.

For Bjarni, Herjolf’s defection also raised questions concerning the future of the shorebased side of his business and he saw two alternative courses of action. Either he could write his father off as having gone soft in the head by following that lunatic Eirik the Red, or he could sail his ship and his trade goods west after the colonists.

It seems likely that, in his note to his son, Herjolf included some words of encouragement about the benefits of keeping the family concern together. If Bjarni made it to the new colony with his ship-load of goodies from the homeland, the Greenlanders would surely be ready to pay top prices for them.

Article continues below…

Ten years or so ago I was contacted by a Finnish yachtsman, Tapio Lehtinen, who was seeking assistance with his…

Christian Williams, now 81, is alive, well and going strong in California. To get a handle on this remarkable man,…

A man of Bjarni’s business acumen cannot have vacillated long over such a decision and, rather than unload the knarr, he put his thoughts to the crew for their consideration. The Vikings preferred to run their deep-sea vessels with a limited degree of democracy and, to a man, Bjarni’s shipmates voted to go with him to Greenland.

That they did so in the face of the inevitable tongue-clicking and head-shaking from the usual gang of Job’s comforters on the dock is a tribute to Bjarni’s leadership. The crowd on his knarr were not just a few out-of-work Vikings dredged up from the bars of Bergen and Trondheim; they were a happy crew content to stick together. Above all, they were professionals.

In Bjarni’s day there was no ice to worry about on this passage and, in due course, nature sent him the pleasant easterly he had awaited. For three days and three nights the fair wind held, as Bjarni had been reasonably certain it would. Now they were entering latitudes where, in late summer, the twilight deepens into darkness.

Bjarni knew he hadn’t much farther to sail before he had run his distance as the knarr creaked, dipped and surged along before the fine passage-making wind, but as the third 24-hour period out of sight of land drew to its close, the weather bit back at them.

The easy sailing breeze backed steadily into the north and it came on to blow. Fog drove down on the gale and soon Bjarni was faced with handling his ship through a serious storm. All navigational considerations went, so to speak, out the porthole.

Back then: Tom Cunliffe in the cockpit of his pilot cutter Hirta. Photo: WM Nixon

Surviving the storm

At sea, there are various degrees of heavy weather, the worst being the survival storm. What exactly the wind force and sea state of a survival storm may be depends upon whether the unhappy mariner is in a 10,000-ton motor ship or a 10ft rowing dinghy, but whatever sort of vessel he is sailing, her limitations will soon become clear.

In a regular gale, a well-found sailing boat the size of a knarr can generally continue to make some way towards her destination, wind direction permitting, but if conditions become really bad the only consideration left in the skipper’s mind will be that of keeping her afloat and undamaged.

The last-ditch options have always varied with the type of vessel; the knarr had modest draught and was not fully decked; she also had no pumps, just a lot of dedicated Norsemen with buckets. The best way for her to survive a heavy storm must be to run before the wind, presenting her stern to the seas and lessening their force.

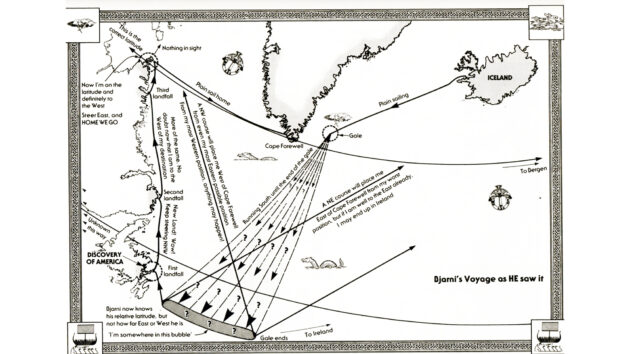

Illustration from Cunliffe’s book Topsail & Battleaxe showing Bjarni’s likely voyage to Greenland. Photo: Tom Cunliffe

Bjarni would have had recourse to these tactics on previous occasions, and that, not surprisingly, is what he did this time. Driving away under bare poles would keep him afloat: it would also run up many miles in, quite possibly, the wrong direction but this could not be helped.

It is by no means unusual for a boat of this size to make 5 knots downwind in a strong gale with no sails set. That means Bjarni was probably making between 100 and 150 miles a day.

Recalculating position

The storm lasted for ‘many days’. Because of the fog, the sailors would have had no idea in the end what the wind direction was, although winds of this nature that endure for such a time in the vicinity of Greenland and the Labrador Sea generally blow from the north-east. Bjarni, therefore, probably went scudding away to the south and west.

Like all gales the ‘northeaster’ finally blew itself out and the sun reappeared. It was immediately obvious to Bjarni that he was way to the southward of Cape Farewell.

Because the concept of even relative longitude was still centuries in the future, his chances of finding Cape Farewell by a straight shot were negligible. He had neither cross-coordinates for his present position, nor for where he was going. For a safe arrival his ship had to be placed on the same latitude as Cape Farewell, but that in itself was not enough.

Cunliffe’s daughter, Hannah, dressed for the weather. Photo: Tom Cunliffe

When he reached that line he had to know whether the Cape lay to the eastward or the westward of his position. If he could be sure of which, then in order to arrive at his destination he had only to run down his latitude in the right direction until he got there.

Starting as he was from an unknown point well to the south, a course of north-east or north-west would place him sufficiently to one side or other of the Cape for him to be confident of which way to turn when he reached the desired latitude.

His reasoning now was quite simple. ‘If I sail north-east I may end up back in Europe, which would be grim for morale. Also, I will then have to work westwards against the westerly winds and the current. If, on the other hand, I trend north-west, the sea may well be empty of land – certainly none has been found so far – but if I find any at all it must lie to the westward of the south Greenland Cape because we know there is no land between the Cape and Ireland. If that happens I will only have to work north until I find the right latitude and then run down it to the eastwards.’

So that is what he did, and the following day Bjarni Herjolfsson became the first seaman from the Old World to officially set eyes upon the American continent.

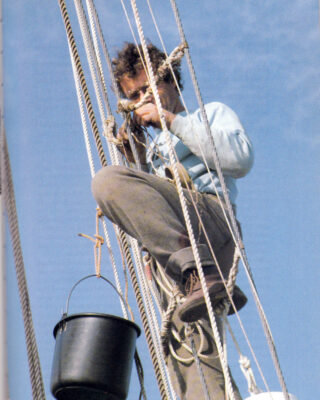

Chris Stewart freshens up the seizings on Hirta’s rig. Photo: Tom Cunliffe

Far away the land lay low on the western horizon. It didn’t look like the description of Greenland that Bjarni had been given and he knew the latitude was wrong, but his curiosity was naturally aroused and he sailed in for a closer look.

The mysterious country was well-wooded and the coast was backed by small hills. Seeing the stands of timber must have made him sit up because Iceland and, for all he knew, Greenland as well, were notoriously short of lumber of building quality, both for ships and houses.

However, with his knarr already deep-laden with high-value cargo, he had no room even to take on samples. Furthermore, the sailing season was growing old and he was anxious to get back to a known position, so he turned his ship’s bow to the northward and bowled away from the coast before a south-west breeze.

Cunliffe’s Hirta was a 35-tonne 1911 gaff-rigged pilot cutter. Photo: Tom Cunliffe

In order to make sense of keeping to his original plan he maintained his heading, and two days later he made another landfall. The hands, ever hopeful, jostled round Bjarni the navigator, asking him if he thought they’d made it.

“No,” he replied. “Greenland is full of snow peaks and glaciers. This surely isn’t it. Also we are many doegr to the southwards of the right height of the Pole Star.” But once again, he noted the wonderful forests that grew green right down to the water’s edge.

Shortly after closing the land the wind died and the knarr was left slatting and banging in the left-over swell. In spite of his desire to investigate what was clearly new ground, Bjarni had made up his mind that it was Greenland or bust for him. Any attempt to go ashore now would waste time and involve him in disciplinary problems rounding up the crew to sail onwards.

The hands, however, had other ideas. A deputation came shuffling aft to where he stood resolutely at the steering oar. “Here’s how it is, Captain,” growled the ringleaders. “The men think we should go ashore and see what there is. We owe it to the whole community, not just to ourselves.”

Bjarni repeated his decision and retreated not an inch. “All that’s as may be,” went on the spokesman, “but we’re going to need water and firewood before too long. We all say you should put in to the shore.”

Cunliffe sailed Hirta to Greenland in 1983. Photo: Tom Cunliffe

Holding ground

But still Bjarni stood his ground. The men were outfaced and dispersed grumbling. Bjarni must have been wondering just how far he could push what was, in reality, a perfectly good crew who were merely reacting to an unusually frustrating voyage when, in the nick of time, a fresh breeze sprang up out of the south-west.

As it came on the spirits of the sailors rose with it as they always have done and always will do. Soon the confrontation was left astern as the ship sailed away to the north-north-west and out of sight of land once more.

They ran northward for three doegr while the Pole Star rose steadily towards the critical mark on Bjarni’s star stick. When it was nearly at the same altitude as at Bergen in Norway, they came upon what they took to be a third country.

A Norse knarr could sail huge distances safely with a cargo. Photo: Tom Cunliffe

This time it was high, barren and topped with a glacier. The hopes of all hands would have soared. However, Bjarni must by now have been confident that he was substantially to the west of his destination and, after a while, he announced that this land was totally worthless.

What his long-suffering crew made of that statement is left unreported by the saga tellers, but just at the strategic moment when the skipper found his latitude and knew beyond a shadow of doubt that he must now turn eastwards, the coast fizzled out and he saw that the land he had been skirting was in fact an island, or at least nothing remotely the size of Greenland.

Any suggestion from the more unenlightened deckhands that they had been cruising northward along the east side of Greenland was thus put to ridicule and, with success assured, Bjarni set his course due east and blasted off out to sea before a rising gale.

Before long it was blowing old boots and the knarr was hard pressed to carry her canvas, but her able crew kept her driving, and driving in the right direction this time. Four days after leaving their final discovery astern, they came upon the imposing snow peaks that back the islands and fjords of Cape Farewell.

Cunliffe’s 1983 voyage reflected that of Bjarni in 985. Photo: Tom Cunliffe

There, lying on a promontory, was a small craft that Bjarni recognised to his great relief as Herjolf’s and, to a hero’s welcome, he brought his ship around what was now called Herjolfness and anchored in front of his father’s new home. Bjarni’s voyage is one of the greatest pieces of deductive navigation of all time, but in addition to his brilliant seamanship, he held his crew together and delivered his cargo in one piece.

He had fulfilled the purpose of his voyage and no sailor can do more than that, but during the long winter nights that followed, many of the Greenlanders began muttering among themselves. It was a poor sort of Norseman, they grizzled, who failed to deliver a full report on such exciting new discoveries. They were quick enough to criticise Bjarni, but it took many years before Eirik’s son Leif put his own life on the line and sailed south-west to find out for himself.

If you enjoyed this….

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams.

Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Note: We may earn a commission when you buy through links on our site, at no extra cost to you. This doesn’t affect our editorial independence.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·